The ‘Ten Tors’ is a notoriously tough challenge that happens every year in Dartmoor. As the name suggests, it involves walking up ten different hills in the National Park.

Grant winner Emily Woodhouse had done that before though. Several times. She wanted a bigger challenge.

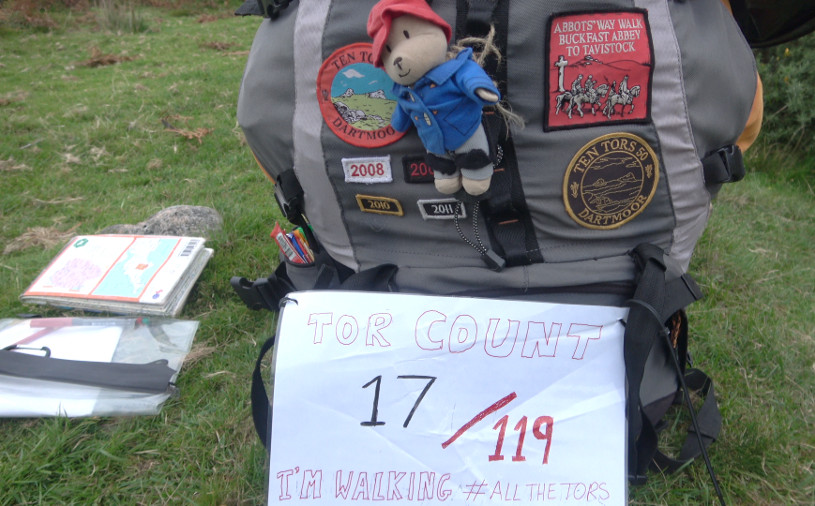

She decided to try walking up every tor on Dartmoor. All 119 of them. On her own. In one go. Carrying all of her own food.

This would have been a remarkable feat of endurance in itself, but the fact that she did it in the most appalling of weather is testament to her determination (not to mention her navigational abilities).

Emily’s account makes for grim reading but hats off to her for seeing her challenge through to completion.

[one_sixth]–[/one_sixth][two_third][box]

The Next Challenge Grant

Emily’s trip was supported by The Next Challenge Grant, an annual bursary for aspiring adventurers.

It’s funded by me – Tim Moss – several other adventurers and crowdfunded public donations.

Since 2015 it has supported 50 different expeditions with awards from £50 to £800.

[/box][/two_third][one_sixth_last]–[/one_sixth_last]

The ‘All the Tors’ Challenge

by Emily Woodhouse

What are Tors?

A tor is a granite outcrop, usually on top of a hill or mountain. In Scotland people bag Munros, in the Lake District they collect Wainwrights and on Dartmoor they bag tors. The task is complicated a little since there is no strict definition of what “counts” as a tor. Wikipedia will tell you that there are over 300 tors on Dartmoor, yet only just over 100 are on the Ordnance Survey map.

Most people go by the map. You can tell if someone’s a Dartmoor Nerd by their response to the question: “What’s the highest tor on Dartmoor?” If it’s longer than two words, it’s time to smile politely and back away slowly.

Why walk all the Tors?

I have been living on Dartmoor almost all of my life. The full story of my romance with the moors can be found here, but All The Tors really began life with Ten Tors.

The Ten Tors Challenge takes places on Dartmoor once a year. Teenagers from the local area train for months to be able to lug their backpacks around 35, 45 or 55 miles – wild camping overnight. Always a glutton for punishment, I did the challenge four years in a row. My team even beat a couple of speed records. But I went to university with a question lingering in the back of my head: “I wonder if it’s possible to do all the tors in one go?”

Fast forward several years and I’m the youngest member of our local Mountain Rescue team. This year (2018) marked the team’s 50th year and my 25th year of existence. It was exactly the excuse I needed to think seriously about All The Tors Challenge. I started route planning and applied to the Next Challenge Grant.

Getting to the Start Line

The planning stage was far more thorough than I’ve ever done for an adventure before. Usually I’d prefer to just set off and see how long it takes. Instead, I was buried in spreadsheets and logistics. The route I’d managed to create between the 119 tors looked like it would take me two weeks or less. Then Dartmoor National Park asked if they could be involved and I had to move the start/finish point to the Visitor Centre in Princetown. Then the firing times were released six weeks before my intended start date. I had to re-route again to avoid being shot.

Finally, the challenge fell into place. I had a start time, a start place and a fixed route. It was going to take me 10 days to complete the 300km, carrying everything I needed to survive. As Dartmoor’s new wild camping ambassador, I was going to spread the message of leave no trace. Even so, when the story of my solo expedition hit the local papers, people started to give me ‘helpful’ words of caution. Most memorably, being instructed by an old lady to take a long knife against overnight intruders.

People also told me I wouldn’t be able to carry enough food for 10 days’ walking. But I packed it all into a 60 litre rucksack. My motto is: Be Yourself – Know Yourself – Challenge Expectations. The more people told me I couldn’t, the more I knew I had to try. Although I could barely lift the bag onto my back, I would walk with it.

The tail end of a hurricane

When you plan an expedition, you don’t imagine the weather turning violently against you. Of course, you think about worst case scenarios, but you optimistically don’t expect it to actually happen. I’d carefully planned my route to include as many nice, easy ridgelines as possible. Could I see them? Nope.

I managed to coincide my journey with the arrival of a post-hurricane storm. This meant days of thick fog and windy, wet nights.

“Emily, before you go, you might just want to listen to the radio a minute whilst they do the weather. There’s going to be a weather warning…”

“No thank you,” I said cheerily. “I know what the forecast is thank you.”

Abysmal. The forecast was abysmal. Tail end of a hurricane sweeping straight across Dartmoor and one look out the window to tell me it was thick fog across the moor.

Never had it occurred to me that I might struggle to find any of the 119 tors. But, on day 2, I walked up into the cloud on Hare Tor and never came back out. I had to count every pace I took from 9am to 6pm, just to stay on track. The visibility was so poor that I could only see 10 metres in front of me, lining up bearings on tufts of grass.

I couldn’t manage another 9 days of this. All I wanted was for someone to tell me that it would be alright tomorrow. But there was no phone signal. I was completely alone.

After a windy night, I peeked out of the tent. Fog. Thick fog.

Sunlight, but not for long

I had climbed the highest tor on Dartmoor by 9am that morning. Then, miraculously, the cloud lifted enough that I could see 50 – even 100 metres in front of me. I was jubilant. By the time I’d been round most of the day’s tors, the sun had come out enough for a rainbow. My raincoat was packed away.

I was dancing around and punching the air in happiness, to the backdrop of a stunning panorama over the north moor’s ridgelines. Incredible.

It was such a good feeling that I tried to get back ahead of my route card. Bathing in the sunshine (ok I was wearing a belay jacket for the wind) I started to amble towards Hound Tor and camp. There was a herd of brown cows spread out along the left hand side of the unmarked path that curves around the bog from Watern. The birds were singing. The sky was a glorious blue.

My night on Hound Tor was disjointed. By some fluke of aerodynamics, nowhere round the tor was out of the wind. This would have been fine if it wasn’t forecast at 35 mph wind with 50 mph gusts. In fact, it was so bad that I had to get up in the middle of the night and drag my already-pitched tent round the corner of the tor, as the wind changed direction.

I sat on the floor outside the public toilets at Fernworthy Reservoir (both locked), hiding from the rain. I was wet, fed up of having to walk through bracken to avoid cows and devastated that the toilets were shut.

I was heading out into the great unknown of the east moor and I was almost out of water.

Almost giving up

Crawling on my stomach to stay out of the wind, I peered over the edge of Mel Tor and down into the Dart valley. All I could see was thick gorse and bracken and trees. I was supposed to be walking down to Luckey Tor, near the river, but I couldn’t see it for the undergrowth.

I was stuck. Trapped. Between Sittaford Tor and Lower White Tor, there is a river called the East Dart. Usually it’s fine to cross in several places but I spent the morning walking upstream, wondering which point would be best to cross. But the only option was to walk all the way back to Postbridge, cross on the road bridge, and walk all the way back out the other side.

It was a devastating decision. I had wasted over a hour, added miles to my long day, got even wetter and maximised time walking into the wind.

By some miracle, the rain stopped at about 10am the next day. Within hours the sun had come out and a stiff breeze as drying my clothes. I got to tor 100. The end was in sight.

The next morning was pretty surreal. I ticked off the last two tors, then met a TV crew along the railway track into Princetown. After several takes of interview and walking back and forth for different shots, I was released into Princetown. I ran to the finish line and was amazed to be greeted by a hoard of Dartmoor Rescue Tavistock members and a flask of hot chocolate.

Alone on Dartmoor

Although I’d spent a lot of time on Dartmoor before, I’d never been alone on a continuous expedition for so long. It really struck home how isolating and risky solo backpacking can be. I found constant decision making after sleepless nights mentally exhausting on top of physical fatigue. In low points I was imagining gorse bushes in the fog were cows out to get me – having been charged by a bull early in the challenge.

It felt like Dartmoor did everything she could to stop me from taking away her crown. If I spent all day looking forward to a solid path, I’d get there to find it standing water deeper than my boots. If the weather cleared up, I’d find myself walking into a 40mph headwind. But I think I’m glad it happened that way. If I’d casually wandered around every tor on Dartmoor, it would have taken away something of the magic of the place. For a full account of my battle around the moor, see here.

Thank you very much to the Next Challenge Grant and its sponsors for helping me to inflict this much suffering on myself. You learn so much more about yourself and the world when the going’s tough. Although this was my first solo expedition, it certainly won’t be the last.

[one_sixth]–[/one_sixth][two_third][box]

The Next Challenge Grant

Emily received a £100 award from The Next Challenge Grant.

The money came from me, other adventurers and members of the public. The boots were donated by Keen.

Do you have an adventure idea that you need help with?

[/box][/two_third][one_sixth_last]–[/one_sixth_last]

What do you think? Please do add your thoughts below…