Last month I shared a story on this blog about how depression and anxiety almost stopped our round-the-world cycling plans.

Since writing about it here, I’ve spoken about it on stage, posted it on LinkedIn and even had the story published on my work intranet.

Whenever I’ve prepared to tell the story in a new forum, I’ve questioned why I am doing so. Why on earth am I telling everyone I work with that I had depression? Why am I announcing on a professional network that I suffered with anxiety?

It felt perverse – like I was somehow bragging about having mental health issues – and foolhardy. Surely, this was an inappropriate topic for a work environment.

But the reason I did so is because of the responses I have received every time I’ve talked about it.

Responses I’ve received

The first set of responses, as you might hope/expect, were incredibly kind. Here are some examples:

Cycling around the world is impressive and inspiring. Overcoming and being honest about this is heroic. Thank you.”

“We’ve started reading the book and we’re really full of admiration for the way you’ve included the description of your breakdown. (You also write very well.)”

“We’ve not met and quite possibly never will. You won’t know it but your North Pole book has hugely changed my wife’s life. From never having run before she got the Couch-to-5K app, got fit and now runs 10Ks etc. And she’s now started taking other mums up mountains. They wouldn’t have done their trips if it hadn’t been for you. It has given her a sense of purpose and her life back. I know very little about depression – but if you end up in the lethargy and darkness I believe it brings again – this is to let you know you have had a tremendous influence on people you don’t even know.”

Given that self-esteem was one of the key causes of my problems, those responses were important. I couldn’t have continued without them so thank you to the many, many people who have responded with such kindness.

However, boosting my own ego is not motivation enough to keep laying myself out for the world to see. It is the next set of responses that started that train of thought:

Thank you. I understand your reluctance to spill this, but I can’t be the only one helped by it.”

“I’m so glad you shared what you did. I appreciate your openness and honesty. For someone who also struggles with depression, I’m grateful and inspired by your words.”

“I just wanted to say thank you so much for that post – brave, and so helpful to read; it helps me to see how various things in my life go or can go and gives me real courage for the future.”

“I really suffered some serious depression a few years ago. Indeed, I think it was why I applied for your grant. Anyway, the main reason for writing is to say I really respect you for telling your audience about your experience. I know from other people’s reaction to my experience that this is not always an easy thing to talk about.”

“I’ve had similar experiences with depression and feelings of being overwhelmed by everything. Really interesting to read about your experience of it and I always find it reassuring knowing that other people have had similar experiences of it.”

“What an inspiration that is. Just shows with the right people round you and help from doctors you can get through it. I suffer myself but most don’t realise as I put on a happy front.”

Loads of people have replied to my articles, emailed me out of the blue or collared me after a talk to share their experiences or thank me for sharing mine. It’s truly remarkable how many people are affected by these issues.

Such responses are not just limited to those who have suffered themselves. I have had many other comments from people who haven’t suffered but felt like now they had a better insight into what depression was actually like:

Although I have never personally suffered with depression I am growing more conscious of how it strike anyone sometimes without warning. I also think it’s so important for people who have a high profile on social media to occasionally show the side away from the lens/post and share the challenges that they face.”

“A beautifully written insight into how depression can sneak up on you and knock you completely off track without any obvious reason. The way you have written this is so enlightening for anyone who has never suffered depression but is struggling to understand the behaviour of someone close to them, that I would like to share it with patients (I’m a GP) who struggle to explain it themselves. I’ve never read anything before that gives such a clear and honest and understandable account.”

The comments above all hint at the importance of talking about this stuff. Others spell it out directly:

Thanks for sharing your experience, mental health is close to my heart and should be spoken about more, so people who suffer don’t feel they have to hide it.”

“Hi Tim, it’s rare to read such an honest blog post as this and I’m sure it will resonate with more people than you can ever guess. It’s a difficult topic, but it shouldn’t be. Personal accounts like this help to remove the stigma from mental health and the internet needs more of them.”

“I found your blog post very moving Tim and good on you for being so open about your depression. There is still such a stigma around mental illness and it needs to be taken much more seriously.”

“Thanks for writing this. It is so important that people write about mental health and the gap between ‘adventurers’ and ‘ordinary people’ gets challenged so we all feel capable of adventure, in whatever form that takes.”

“I imagine writing this was up there with one of the hardest things you’ve done but it’s just as inspiring as all your adventures. It’s super important to talk about mental health issues. You don’t often hear people being so honest about it especially among the adventurers out there. So bravo!”

“I’ve never written to you so far. Your post got my attention and I really felt like I had to get back to you on it. Congratulations for your courage to talk openly about depression. It takes an immense strength to come out and do it. I hope more and more people in the world would follow that example and one day soon it will become normal to talk about mental health issues.”

What conclusion could I draw from this other than that speaking about my mental health issues can help other people?

And how could I respond to that other than by continuing to talk about it?

Writing about it in a professional environment

On Monday, I uploaded my story to LinkedIn, a professional network of online CVs. Part of me knew that it was stupid because most of the people reading it would be professional contacts who don’t want to hear about their peers’ personal problems. I don’t normally start my job interviews by telling potential employers that I used to cry behind my bed.

But I also knew from all of the comments above, that just because someone wears a suit or puts on a professional façade, they are no less likely to suffer similar problems.

And just as I was motivated to tell my story in the adventure community because I thought people might not expect a ‘tough adventurer’ to have mental problems, I figured that LinkedIn would be the last place anyone talked about depression and anxiety, which made it all the more important to do so.

I subsequently discovered that it was Mental Health Awareness Week. That fact spurred me to share the same story on my work intranet (I work at a pretty progressive firm where our internal social media platform has an entire section for people to share their mental health stories). I knew some of my colleagues had already seen the article on LinkedIn so the cat was already out of the bag.

Within an hour, I got an email from head office asking if they could put my story on the front page of the intranet. I have subsequently had several emails from colleagues – some with whom I work, others I’ve never met – and multiple conversations by the photocopier, all in a similar vein to those expressed above.

Talking about it on stage

Lots of people have told me that it was brave to talk about my depression publicly and on social media. It didn’t require any bravery though. As you can see from the responses above, I have received nothing but overwhelming kindness in response.

What did take bravery, however, was talking about it in front of a crowd of people, which is what I did at the Cycle Touring Festival two weeks ago.

My wife organises the festival and I help. We don’t normally talk about our own trip because there are plenty of more interesting people than us at the event and, besides, it seems a bit self-indulgent to sing at your own party. But after four years of running it, we decided that this was the year that we’d take the stage (entirely unrelated to the recent publication of my book about our bike trip).

I was stressed all of Saturday and I couldn’t work out why. In hindsight, it was painfully obvious that I was terrified of telling my story to a room full of people. I didn’t know how I would respond and whether I would make it through without breaking down.

The talk, like the book, was 95% about the people we met while cycling the world with just a tiny bit of depression stuff at the start. But that was where all of the tension lay.

Much of the story was as I have written it in my book, although I did give a little more detail about the actual build-up to my anxiety. This is what happened after we cancelled our training trip as I was starting to struggle:

“I remember going to play netball with Laura’s work team one evening. The referee blew her whistle and said I’d fouled someone.

What? I thought. I didn’t foul anyone. Why is the referee picking on me? Why doesn’t she like me? I’m sure I didn’t foul anyone. Or maybe I did foul someone? Maybe I am the kind of person that fouls people on a netball court? Maybe I’m a bad person?

It was a ridiculous thought process to go through but, at the time, it felt sufficiently important that there were tears running down my cheeks as we cycled home through the streets of London.

One Saturday a few weeks later, Laura and I were planning to go out for a walk. We weren’t sure where to go: should we walk from home or get in the car and drive somewhere first? And if we’re going to head out, I thought, we should take some food but then we don’t actually have any food in. We could eat in a cafe but I’ve not got much money so maybe we’d better go to the supermarket first. But that’s stupid, we shouldn’t need to go to the shops just to go for a walk, maybe we shouldn’t go out at all.

It was utterly mundane and unimportant but it started to overwhelm me and I had to leave the kitchen. I found myself walking into our bedroom, where I sat on the floor in the corner. I squeezed my eyes shut tight and rammed my fingers into my ears so that I couldn’t see or hear anything. Perhaps if I could shut the world away then I’d feel better, I thought.

It worked and my problems immediately fell away. Except, of course, at some point Laura came into the room and found her husband curled up in a ball, rocking backwards and forwards, unresponsive.

But what must have been a shocking scene when Laura first found me, soon became shockingly normal; and the situation quickly moved from tragic to comic. Friends came over for a barbecue and I had to hide behind the bed while Laura served me chicken wings on the bedroom floor and everyone had to sort of pretend they didn’t know I was there. My parents came to visit and they had to come into our bedroom to speak to me, while I sat on the floorboards looking up at them like a child. I would go to the supermarket, immediately get overwhelmed by choice and find myself frozen on the spot and crying in the aisles with an empty basket in my hand.

A year earlier I had crossed a desert, run an ultramarathon and set a world record, and now I was reduced to hiding behind beds and weeping in Asda.

The tragicomedy continued though because I still insisted that I would be OK to cycle around the world. But Laura helped me to realise that I wasn’t well so we delayed our plans while I got help: drugs, group therapy, counselling, mindfulness, more drugs and CBT.

A year later, we got our round-the-world plans back on track, packed our panniers and set off to cycle to Australia.”

As I neared the end of this part of the speech, I thought that I would manage to get through it like a pro, but emotion got the better of me and I choked. I just got the words out in time for an entire marquee of people to rise to their feet in applause.

Wow @NextChallenge just got a standing ovation from everyone @CycleTourFest after relaying how him & his Wife got him through #depression

— Tyresandtents (@tyresandtents) May 5, 2018

That might have been the best talk I’ve ever listened to. Tim and Laura Moss @CycleTourFest Quick! Buy @NextChallenge book “With the Sun on our Right” about being human and riding round the world. pic.twitter.com/ea023b7ERn

— lee craigie (@leecraigie_) May 5, 2018

It was one of the most powerful experiences I’ve ever been through. I poured my heart out on stage and, in response, 200 people stood up and applauded. I am so thankful to everyone in that tent who’s beaming smiles and clapping hands gave me the comfort I needed at the very moment I needed it most. I still can’t think about it without welling up.

But, as with the responses to my articles, although the kindness was important – necessary even – it was the conversations afterwards that confirmed I had done the right thing. Person after person found me over the rest of the weekend to tell me how much they appreciated what I said.

One conversation in particular stood out. I had seen the guy before but never really spoken to him, perhaps in part because I found him intimidating. He was a much more blokey bloke than me. In fact, although I hadn’t known he was in the audience for my talk, he was exactly the kind of person I was worried about crying in front of. The kind of person I imagined would think I was being pathetic or a snowflake, and would want to hear about the derring-do of my adventures not the weeping.

After the talk, he found me at a quiet moment and said:

‘Those things you said on stage: the insecurity, the hiding away, not wanting to talk to people. That’s me right now.’

I will never forget the conversation that followed because he was the last person I would have expected to have mental health issues.

But perhaps that’s what people said about me.

[box type=”custom” radius=”2″ border=”#b2b2b2″]

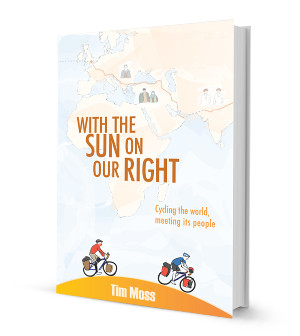

With the Sun on Our Right

Now on sale!

[one_third]

[/one_third]

[two_third_last]

The full story of Tim and Laura’s 13,000-mile round-the-world cycle

330 pages plus 8 pages of colour photographs

Exclusively available on this website.

[one_half]

[button color=”gray” link=”http://thenextchallenge.org/books/sun/” size=”bigger” align=”center”]Read more[/button]

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

[button color=”green” link=”http://thenextchallenge.org/books/sun#buy” size=”bigger” align=”center”]Pre-Order Now ➜[/button]

[/one_half_last]

[/two_third_last]

[/box]

What do you think? Please do add your thoughts below…