As well as enjoying the drama of England’s progress through the group and knock-out stages of the World Cup, it’s also reminding me of where I was this time four years ago: cycling across Malaysia.

Our time in the country did not just overlap with an international football tournament, it was also Ramadan, which made long days of exercise quite hard because there was nowhere to buy food or drink.

Here are two short pieces from my book about our round-the-world trip. One covers cycling during Ramadan and the other covers cycling during the 2014 Football World Cup.

Cycling in Malaysia during Ramadan

By the time we reached the first town in Malaysia, Kuala Perlis, we were long overdue for some breakfast, but despite it being mid-morning, everywhere was shut. Not just the cafes and restaurants, but the supermarkets too. Nothing was open, because it was Ramadan.

The official religion of Malaysia is Islam, which means that for one month each year, no one eats or drinks while the sun is up. Shops stay closed all day and restaurants only open at sunset. That year, Ramadan ran through August: the middle of summer, when the sun was at its hottest. That same year, two hungry foreigners chose the month of August to cycle the country’s length.

This might be considered poor planning on our part, but the timings of our journey were largely set from the moment we left home. Our summer departure was fixed by the need to finish teaching a school year and attend a friend’s wedding. That meant a blissful European summer and a frigid Turkey. Had it not been winter when we reached Iran, we might have opted to head north through Central Asia, but instead, we chose the warmth of the Arabian Peninsula and India. And now we had arrived in Malaysia during the height of summer, in a month when nowhere sold food or drink during daylight hours.

The issue was exacerbated shortly after our arrival when we crossed over to the east coast, which is the less populated and more Muslim side. We got the quieter roads we wanted, but with the local population more devout than their neighbours on the west, it also meant that everywhere was shut.

‘Everywhere’s shut,’ I declared glumly.

‘Not everywhere,’ Laura said with a glint in her eye. ‘Look.’

She pointed at a familiar plastic façade in the distance with the unmistakable red and white logo of Kentucky Fried Chicken.

We had heard so many great things about Malaysian food, but its purveyors had all closed up shop, leaving us outside in the heat with KFC as the only option. We wheeled our bikes to the entrance and leaned them against the window. There was a sign on the door warning that it was illegal to sell food to Muslims during Ramadan, but even with my big beard, we figured it was pretty obvious that we were from out of town.

It was deserted inside and pleasantly cool. We walked to the counter, me huffing that we were in Southeast Asia and forced to eat fast food, Laura grinning like a Cheshire cat. KFC is her secret vice and she is always pestering me to go. I rolled my eyes and ordered whatever daftly named product on the menu sounded least unappetising.

The next day we found ourselves in the exact same situation: everywhere closed but KFC. With a little less reluctance this time, we cycled straight over, parked our bikes and placed our orders.

‘I can’t believe we’re in Malaysia, with all of its amazing food, and we have to eat KFC every day,’ I said, half-heartedly.

‘Yeah, bummer,’ Laura replied with a piece of chicken in her mouth. ‘Will you get me another drink if you’re going up?’

We ended up eating in KFC, or somewhere similar, nearly every day. After initially going through the motions of right-on, middle class Westerners – convincing ourselves that we were only there because we had to be and did not really like the food – we soon forgot our pretences. In fact, open restaurants and food stores were so rare during the coming weeks that we would punch the air when we saw a KFC sign, knowing that high fat, high salt, high sugar food was just moments away.

I ate more fast food during our month in Malaysia than I had done in the thirty years of my life that preceded it. Like Lidl in Europe, KFC provided an easy consistency in an ever-changing world. Circumstances had forced it upon us, but KFC turned out to be a welcome, air-conditioned sanctuary.

Once we had accepted that fast food was our only option, we developed a routine for cycling in Malaysia. We would wake early before the day was at its hottest and cycle non-stop until we found a fast food joint. Sometimes it would get to the middle of the afternoon and we still would not have found anywhere that was open. In those instances, hot, hungry and thirsty, all communication between the two of us would have long since ceased. We would pedal blindly onwards, repeatedly squeezing our empty bike bottles over our mouths in the hope that we might have missed a bit last time, and trying not to think too hard about what might happen if we never found another open restaurant. On other occasions however, we would stumble across a McDonald’s first thing in the morning and feel obliged to make the most of it since we would not know how far off the next one would be. That is what happened on the day of the World Cup semi-final.

Cycle touring during the World Cup

Despite not watching a single game until that morning, I had been following the World Cup more closely than any other football tournament in my life. I had been listening to a daily podcast (downloaded on KFC wifi) which discussed all the action from the previous day’s matches in Brazil. I had only seen sixty seconds of actual play, glimpsed in a late night petrol station, but I knew every little detail of what had happened from my radio show.

Having set off at some ungodly hour that morning due to my recurring inability to sleep in the humidity, we had passed a McDonald’s, outside which a crowd of young Malaysians had gathered around a TV screen showing Netherlands vs Argentina. It was only 5am, but we each ordered a Big Mac Meal and settled down to watch the game.

I am not a football fan and, under normal circumstances, would not follow it at all, but keeping up with the World Cup somehow felt like a small connection to home. Despite being on the other side of the world, I could live the same drama along with the rest of my country and share its pain at our inevitable early demise. I could email my dad to get his prediction of when England would crash out and ask if he had seen Germany thrash Brazil. It meant that I could be a part of something that was more than just riding a bike, even if in this case, it was just kicking a ball instead.

[box type=”custom” radius=”2″ border=”#b2b2b2″]

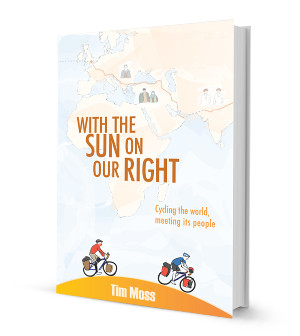

With the Sun on Our Right

Now on sale!

[one_third]

[/one_third]

[two_third_last]

The full story of Tim and Laura’s 13,000-mile round-the-world cycle

330 pages plus 8 pages of colour photographs

Exclusively available on this website.

[one_half]

[button color=”gray” link=”http://thenextchallenge.org/books/sun/” size=”bigger” align=”center”]Read more[/button]

[/one_half]

[one_half_last]

[button color=”green” link=”http://thenextchallenge.org/books/sun#buy” size=”bigger” align=”center”]Pre-Order Now ➜[/button]

[/one_half_last]

[/two_third_last]

[/box]

What do you think? Please do add your thoughts below…