My friend Kate Rawles, author of The Carbon Cycle, is in the process of writing her second book (details here).

While doing so, she has been reading mine. And that prompted her to ask about my writing process:

“…have finally started reading your book and am really enjoying it. It’s a very engaging, clear style. I have a million questions already, mostly about process.

I’ve written elsewhere about how I found the time to write my book while working full time, but here is a little detail about the actual method I followed.

1. Did you plan the structure in advance or just start writing?

I just started writing. However, that is not to say that I did not spend a lot of time on the structure.

When I started writing, it wasn’t at the beginning. Because I had to fit my writing into lunchbreaks at work, I couldn’t afford to waste any time battling writer’s block, so I just wrote whatever I was inspired to write at that moment.

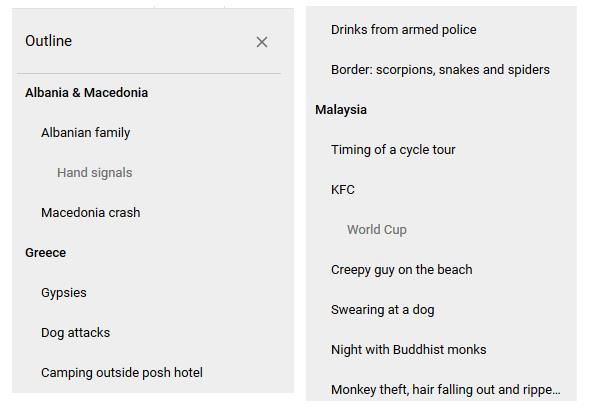

This might have been hard to keep track of, but I used the ‘outline’ feature in Google Docs to organise everything into headings and subheadings. Like this:

So, if I wanted to write about the aftermath of Hurricane Rita one day and the Korean Four Rivers bike trail the next, I could jump to the appropriate subheading and fill in the details.

The entire book was built around ~145 anecdotes/observations/encounters/thoughts. 145 subheadings, like the ones shown in the screenshot above. I spent a year building those up, by the end of which, I had around 120,000 words (i.e. enough for a full book).

I then spent another year working on the structure of the book and weaving the anecdotes together into a coherent narrative. That meant making sure all these chunks of stories linked together and ensuring they complemented and built on each other (rather than repeating or contradicting).

A further six months were spent in editing.

2. Was it based on journals?

Laura and I both kept journals, and these were indeed used during the writing process. But the book is not “based” on them.

Those journals are a daily record of things that happened and our feelings at the time. I could have based the book on those journals, but it would have made for an uninspiring, linear narrative.

Instead, I read through the journals and made a list of interesting people, incidents and ideas, which fed into the 145 subheadings mentioned above. But, ultimately, I started writing with a blank slate.

Similarly, I had 30 or so blog posts that I could have drawn from. I tried to make use of them, but they tended to be standalone pieces that did not fit with a longer story. I think I ended up using just three blog posts as the basis for content in the book.

In addition to the journal, I also had the following:

- A spreadsheet which tracked where we stayed each night. This was surprisingly useful when trying to piece together bits of our story.

- Updates from our Twitter accounts. These were often quite revealing of our mental state at the time. I remember India being great fun but, at the time, I wrote: “Not enjoying India one bit. Can’t wait to leave. 4 days to the Nepalese border.”

- Laura. She often noticed things that I did not, remembered things I had forgotten and had different perspectives on our experiences.

3. How did you decide what to leave out?

This is a telling question. I viewed the decision as: what should make it in, rather than what should be left out.

There is no way that I could have included even a quarter of our experiences and attempting to do so would have made for a very boring book.

Instead, I worked on the assumption that nothing made it into the book unless it:

- Would be interesting to someone else, AND,

- Fitted with the story.

That meant that whole days, weeks, months and countries were omitted from the story. If there was an interesting anecdote on Day 27 and the next one wasn’t until two countries later on Day 39, then I would not say anything about the intervening 11 days. They’re boring!

Instead, I would do one of two things:

Either, I would link the two anecdotes by saying something like “a week or so later…” (like in Chapter 10 when we get ambushed by dogs at lunch time then, “a few days later”, stop for the evening with a farmer).

Or, I would just take a liberty and pretend the two things happened on the same day (in reality, our stay with the Iranian Red Crescent and our stumbling into the nuclear compound happened a week apart, but in Chapter 17 they are on consecutive days).

Similarly, if two people from different countries exhibited similar behaviours then, rather than writing about the same thing twice, I might merge them into a composite character (Hadi, in Iran, is one such character). In fact, I even split one person we met into two different characters: John from Border Patrol and Sam the gun nut are both based on the same person. The story just worked better that way.

Having started from nothing and only included interesting stories, I then culled around 20,000 words’ worth of stories that I still thought were interesting but that did not fit into the flow of the book. This was hard to do, especially when I might have spent weeks researching and crafting a section.

I drew some consolation for this by including those “Deleted scenes” in a separate pack of Bonus Material and/or using some as promotional blog posts.

So, while there are loads of thoughts and anecdotes that I would have loved to include, hopefully what’s left is the most interesting bits.

Having written all of this, I am sure that I did not start out with such clear thinking and I have no doubt that many better books than mine have been written with completely different approaches.

What do you think? Please do add your thoughts below…