A-level student Alex was originally awarded a Next Challenge Grant in 2020 to walk the Cornish coastline, to raise awareness of the need to reduce our dependency on single-use plastics. The Covid pandemic intervened and the plan changed: instead of the Plastic Plod, Alex proposed a Plastic Paddle. With three friends, he paddled 120 miles along the River Severn, collecting plastic fragments and interviewing Members of Parliament and members of the public about the impact of Covid on their lives and on the waterway. His trip is a fantastic example of “Adventure Plus”: using an expedition to conduct citizen science and highlight a wider message. All the more impressive given his young age!

(Alex went on to give a talk about his trip to the Royal Geographical Society, which you can watch here)

The Next Challenge Grant is a crowd-funded adventure grant which has supported over 70 adventures since it was founded in 2015. Applications for 2023 are now closed, but you can read about past winners and donate here.

Microexpedition for microplastics

by Alex McDermott

My name is Alex McDermott. I’m an A level student at Ecclesbourne School in Derbyshire. I’m also a former Member of UK Youth Parliament, as well as being a rep for Surfers Against Sewage and a keen kayaker. As the first lockdown lifted, I quickly planned a small expedition at short notice. With my A level geography course starting a few months later, I thought it would be great to venture into the outdoors with three other mates and do some positive fieldwork at the same time. So, we paddled for 120 miles on the longest river in Britain: the River Severn. A micro-man on a micro expedition for microplastic!

People and the River Severn have been linked for a very long time. People who live on it. People who work on it. People who play on it. And people who look after it.

We were interested to see how they had been impacted by Covid. We interviewed 22 people in all, sometimes on video, sometimes in person. Although Covid is a single virus, we found many contrasting views about its impact on the river. From Alison – a local from Montford Bridge and keen dog walker – who told us that Covid has cleared out the hordes of strangers whose dogs fouled the riverbanks, to her next-door neighbour – ‘Hire a Canoe.com’ – where idle canoe trailers and empty tents showed a small business devastated by the lack of demand Covid had created. At the Severn Motor Yacht Club, the retired, grey-haired adventurers were thrilled to see young lads out camping and doing science during a global pandemic. Their very casual attitude towards social distancing, as they welcomed us into the bar, seemed at odds with the man in a hazmat suit and visor outside who was cleaning their boats that hadn’t been used since lockdown. At Diglis, the lockkeeper told us that the reduced human activity on the river and undisturbed fish ladders meant that he had observed much greater numbers of salmon. It appeared that Covid meant many different things for the people of the Severn.

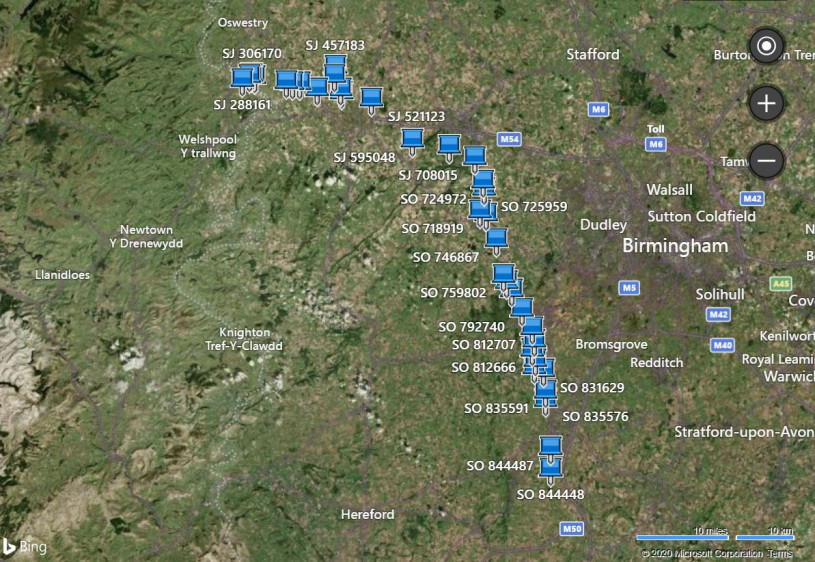

In contrast to the benefits for the salmon population, we witnessed a negative impact from nature being left undisturbed during lockdown. Himalayan Balsam is an invasive species, and local organisations have been involved for some time in trying to reduce its impact. Severn Rivers Trust asked us to locate the balsam on our path, as the Trust had struggled to monitor and maintain the riverbank during lockdown. During the journey, we produced a balsam location chart which we handed over to the Trust. This introduced me to the idea of citizen science and the huge opportunities it offers. We’re more likely to care for our rivers if we understand and engage with them more.

When I first started canoeing on my local river, the Derwent, I was shocked to see how much plastic was caught in the trees and banks and it motivated me to get more involved. We counted and categorised all the plastic pieces we saw in trees, bankside and in the river, in total more than 1700 individual items with 735 in one day near Coalport – the largest, embarrassingly, being a kayak! Alongside microplastic, we wanted to see if microplastic pollution was a big issue on the Severn. In 2019, Greenpeace had investigated the microplastics in 13 UK rivers, including the Severn. We replicated this study in the same three locations on the river using a cheap homemade version of the Manta net, suspended from bridges to capture surface microplastics, and to compare findings after four months of lockdown. We found more biobeads – used as part of the water cleaning process – than Greenpeace did, possibly due to the heavy flooding in February 2020 which released poorly contained biobeads from the settling tanks into the river. Nurdles were more common in our July 2020 study compared to the Greenpeace one in March 2019. Nurdles are uniform pieces of plastic used as a precursor to injection moulding of everyday plastic items. Again, perhaps this is a result of the significant flooding washing plastic from commercial sites and roads into the river.

We collected far fewer plastic fragments – coming from bags, straws, and other litter sources – than the 2019 Greenpeace study. Fewer people out during Covid lockdown may have meant less littering, and therefore less plastic in the rivers. Changing behaviours – whether river access, single-use plastic or bio-bead containment – is possible – but needs political and public support. Consequently, I was keen to talk to local politicians to ask what they felt were the key issues on the River Severn.

We interviewed the MPs for Worcester, Gloucester, and Montgomeryshire. Perhaps surprisingly for politicians, they all agreed on one thing. As impact goes, COVID was not the only show in town. With a history of flooding, the River Severn sees regular widespread damage to its surroundings. Floods were abnormally bad last winter: at Diglis, the water had reached 5.1 metres high – almost double the normal levels. MPs told us that Ironbridge had been devastated by floods, but the usual summer tourism had been crushed by Covid, so the need for government investment in flood defence was essential. It appeared that the impact of flooding on their constituencies was a more serious, and longer-term threat than Covid, but had received much less government attention.

This made me reflect on the similar question at global scale, comparing the world’s enormous response to Covid, to the seeming lack of excitement over the existential threat of global warming. So, that is the story of my journey on the Severn. I was surprised by what we’d found. Some types of plastic have reduced due to less human activity. Salmon at Diglis and swans at Montford Bridge have benefited; but so has the invasive Himalayan Balsam. On the river, people’s views are diverse – but it’s clear that Covid might not be the number one threat.

So, is Covid the villain of my story on the Severn? What is clear, as pointed out recently by the UN Secretary General, is that the pandemic has created a critical juncture. This presents a fleeting opportunity to make change for good, but we must act now.

What can we do?

How does the story end? Well, it’s up to us. Campaigns such as ‘Paddle Peak’ and ‘Clear Access, Clear Waters’ aim to achieve more access to UK waterways so that people can understand rivers better and know how to care for them. So, how can you help? There are two main ways to get involved.

Firstly, sign the CACW petition on your phone. CACW is a British Canoeing campaign to support wider access of waterways, because people who are more engaged, will want to protect their rivers better.

Secondly, why not use the template provided on the CACW website to contact your MP (www.clearaccessclearwaters.org.uk)! Small changes – made in lots of places – make a big difference!

Thank you so much to those who donated to the grant! Without initiatives like the Next Challenge, it would not be possible for many young adventurers like myself to experience these fantastic opportunities.

See you on the water,

Alex

What do you think? Please do add your thoughts below…